A book review of David Dickson’s Old World Colony by Elwood H. Jones

David Dickson, Old World Colony: Cork and South Munster 1630-1830, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 2005

David Dickson studied the historical records of southern Ireland over 200 years from 1630-1830 in a book he called Old World Colony. The title suggests that the methods used for settling colonies in the New World, such as Virginia, were developed in Ireland. This is my favourite book on Irish history.

There is an advantage in seeing history in long sweeps of time. It is possible to discern what was important from what is interesting. Over the long term, we can observe changes in institutions, follow the impact of major disruptions. English settlers, assisted by English legislation, decrees, institutions and leadership, were dominant in Ireland, just as they were in Virginia before 1776.

For our area, this long view of southern Irish history, has added importance. In the 1820s, Irish emigrants came to Peterborough and area, a quarter century before the more famous Irish emigrations tied to the Irish famine. Dickson chose to have his long-term history separate from the Famine years of 1847-1849 to allow a clearer insight into what happened in the 1820s where in his view the most important changes occurred.

For the most part, Dickson’s story is about the people who stayed in Ireland. In trying to assess how eager the emigrants were, it is worthwhile to see that emigration was part of the history of this part of Ireland. In the 17th century, the coastal part of Munster had a thriving fishing industry tied around sardines; later, many sailed from this area as part of the fishing in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. The agricultural goods produced in those areas close to the Blackwater and other rivers, or within close reach of the coast were exported to Dublin, England and western Europe. In many years Irish left for harvest seasons in Spain.

The main point is that those who emigrated from southern Ireland with the Robinson settlers of 1823 and 1825 were part of the wider world and not from a backward backwater. The pressure to emigrate might have been widespread, but the likelihood of emigration depended on family strategies. Those most likely to emigrate had to afford the costs of uprooting, sailing, traveling in the New World, and settling on land that would not produce in its first year.

The main characteristics that we usually associate with emigration were developed before the end of the 18th century. The hierarchy of rural architecture was well-established; the landowners were at the top, the tenants had clear leases, and the sub-tenants, gneevers and labourers were landless. Success seemed tied to security of land arrangements, and a main measure of success was whether people’s income rose faster than the cost of living, or how they could weather crop failures.

There were many changes in the half century after the 1770s.

As late as 1790, south Munster and Cork were considered grazing country. Dairy farming and butter production was important on the mid-Cork highland. In 1810, the plough had returned to the low-land and the Rev. Horatio Townsend observed that in north Cork graziers and dairymen were yielding to smaller producers who were combining sheep with tillage farmer. Wheat cultivation increased aided by the increased waterpower of the Blackwater and other rivers. One result was five large flour mills in northeast Cork, by the 1820s Fermoy was Munster’s largest inland market for wheat and oats. With the rising cereal prices, there was a big increase in spring-sown oats. There was an export trade from Yougal and Dungarvan to Britain from the 1790s to the 1830s.

The best cultivated parts of Cork contained wheat and barley, and just west of Cork tillage and dairying were considered complementary; in 1798, on average, each farm in this area had 5.2 cows, 4.2 acres of potatoes, and 11.9 acres under wheat and oats. Along the southern coast, long dominated by barley and potatoes, wheat emerged as a cash crop, accessible to the new grist mills. In the Bandon valley there was continual growth in tillage, partly assisted by inland migration from the southern coast willing to move on marginal lands.

As tithes were tied to produce, Dickson was able to analyze changes across the region; tithe revenue nearly tripled between 1788 and 1826. This growth reflected rising prices, increased acreage under crops, the expansion of cereal production, and the extension of potato cultivation.

Corn production was ubiquitous across southern Ireland. Local farming societies spread information about new trends and supported plowing matches by 1813. Despite what authors said in pamphlets and books, Irish crop yields compared favourably with elsewhere.

There was no massive change in productivity between the 1770s and 1840s. This was possible in an era of increased productivity and growing population because of improvements in husbandry, ability to move on to inferior lands, and the increased labour force.

There were also changes in seeds. For example, the five favoured varieties of potatoes in the 1730s had largely disappeared by the 1780s and completely by the 1810s. This surprised Dickson, since farmers usually used the smaller potatoes from the previous crop for seed in the new crop. This happened too with wheat, barley and oats, but this may have been a consequence of the periodic importation of grain in years of local crop failure. Fertilizers and better roads also contributed to agricultural improvement.

By 1815 the lighter Scottish swing plough replaced the wooden plough especially around Cork and points east. Dickson doubts that this happened as widely as enthusiasts suggested as there were large initial costs for farmers, and the need for blacksmiths and ploughmen to learn new skills. Even in areas such as Kerry and west Cork where the mule and spade ruled, innovations in tools were valued.

By the 1770s, the potato was becoming the main food for eleven months of the year, as oatmeal and barley became less important for summer food. Dickson says that there were several reasons for this. The economic position of the rural labourer was eroded by sluggish wages, higher rents for gardens, and smaller acreage for his family. With too little room for corn cultivation, cabbage and kale were cultivated for the May to August food supplements. Second, there were improved varieties of potatoes that were hardy, edible and easily stored. Third, during the time of war between England and France that lasted until 1815, high prices for oats driven by export demand meant that small producers were more likely to export grain rahter than consume grain locally. Even so, the lower reaches of southern Irish society could supplement their diets with items such as fish cabbage and salted meat; in the 1820s, these were beyond the reach of labourers, rural or urban.

The population of Cork and Munster may have been about 350,000 around 1750; by 1830, it was 1.1 million. By various means, Dickson concludes that the population was doubling every 44 years. In colonial situations, population growth was tied to immigration. However, in this area immigration was modest. There were regional migrations, particularly to Cork which drew from a wider area as time passed. There was some migration to England, and in the western areas there were fishermen. In 1775, four ships sailed from Munster for the United States middle colonies, but such sailings were rare. Smallpox was less virulent, and inoculation was common after 1740. Grain imports were regular and rice and Indian meal were imported after 1801. By pre-industrial standards food supply was good even in the face of rapid population growth across the 18th century.

The English colonial strategy of the seventeenth century aimed at “military pacification; cultural assimilation and economic development.” (497) The first was accomplished painfully, and the second ambiguously, and the third definitely. With the addition of the potato, the agrarian economy was dynamic. Socially, the class structure was complex and income was distributed inequitably. However, by the 1820s the future of the bottom of society was bleak. Because of the cumulative effects of the previous half century rural labourers and even those with a little land lacked flexibility.

Dickson rightly notes that the 1820s, not the 1840s, was the economic and cultural divide of southern Ireland. Comparatively, there was a larger loss of population in Munster than in either 1740s or 1840s. The emigrations of the 1820s slowed the population growth of the 1830s. The political nationalism that emerged was a consequence of the compressing of two previous centuries of experience. The Robinson emigrants came from Munster.

The backdrop of the Robinson emigrations of 1823 and 1825 to Upper Canada was a small part of the 1820s loss of population. In the long view, the factors that brought hardships in the 1820s were entrenched. The high inflation following the wars with France, the underemployment partly related to family growth, the technical improvements, the high cost of land, were all factors that caused distress to some people. However, wanting to leave was not enough to encourage people to leave. In the Blackwater area of southern Ireland, emigration became feasible because the Robinson experiment provided free passage and guaranteed support in the new world.

Some local historians in the Peterborough area have claimed that the Robinson emigration was one of many assisted emigration projects. This fails to see that the Robinson emigrations of 1823 and 1825 were experiments to see if the English Parliament, with the resources of the Colonial Office, the Royal Navy, the military and the local authorities in Upper Canada could cover all expenses of the migration of up to 2,000 emigrants and still prove to be financially profitable to England while relieving some extreme poverty. The British Parliament concluded that the Robinson experiment of 1825 did not meet expectations and it was never again tried in a non-military setting.

What happened instead was that the British Parliament used taxation, notably with versions of the Poor Act and changes in emigration policy encourage landlords, parishes and community groups to subsidize emigration. There were hundreds of assisted emigrations, but none were like the Robinson experiments which were completely government projects hoping to assist very poor emigrants without other means of support. Even at the peak of the Famine migrations of the next generation, 1847-1851, the government avoided assisting emigration.

The Robinson experiment was a high-minded project with superb and experienced leadership but was deemed a failure because it did not prove that centrally planned emigration was economically superior to a system of family planned and landlord assisted emigration. People were willing to make sacrifices in order to start a new life in the colonies.

Elwood H. Jones, archivist Trent Valley Archives.Visitors are welcome at Trent Valley Archives, 567 Carnegie Avenue, and to its events. See their webpage www.trentvalleyarchives.com. He is also on the board of Nine Ships 1825 Inc.

Book Information

David Dickson is associate professor of modern history at Trinity College Dublin.

Published by: University of Wisconsin Press; 1st edition (June 22 2005)

Pages: 744

ISBN-10 : 0299211800

ISBN-13 : 978-0299211806

For purchase on Amazon (Canada):

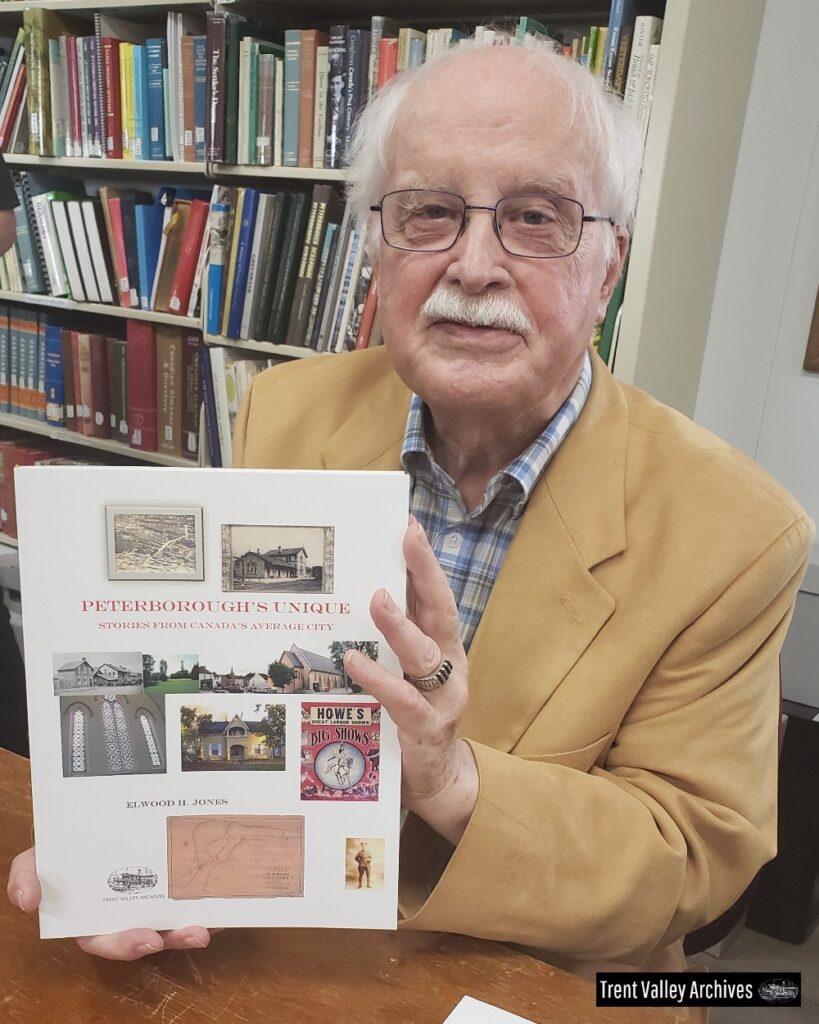

| About the Blogger |

|---|

| Elwood Jones is a prominent Peterborough historian, esteemed member of Nine Ships 1825 Inc., Professor Emeritus of History at Trent University, and archivist at Trent Valley Archives. With a prolific career, Elwood has authored a dozen historical books, several pamphlets, and numerous articles, including over 300 columns for the Peterborough Examiner. He also serves as the editor of the Heritage Gazette of the Trent Valley and has been a long-time editor for the Peterborough Historical Society and the Canadian Church Historical Society. |

Hi, why do we consider that the Robinson experiment was not successful. Did many of the settlers fail? I have seen the list of families, most of whom were destitute, and I would imagine that they would jump at a chance for a new life. But maybe they hadn’t the skills or knowledge to succeed.

This is a good question. The success of the “political experiment” has to be judged by how it affected British policy towards emigration. The British government mostly left emigration to individual decisions but on a few instances after 1815 gave modest support to certain group emigrations. Sir Robert Wilmot Horton, who recruited Peter Robinson to quarterback the 1823 and 1825 experiments, with some influence as a Member of Parliament and as an undersecretary in the Colonial Office, pressed for fully funded emigration schemes aimed at helping displaced farmers. These would be farmers who were unable to renew leases for their farms because of the actions of the landlords and agents. They would be skilled farmers with probably 20 or 30 years experience in farming but without opportunities to own a profitable farm in southern Ireland.

One condition of accepting Horton’s proposal was the creation of a Parliamentary Committee on Emigration who would explore all options including the experience of the Robinson emigrants. However, Robinson needed to produce immediate reports on the financial feasibility, and the necessary reports did not come soon enough; in fact, only by 1842. So Parliament decided that the best option was to let people emigrate with whatever arrangements for support they could muster but not by the Government and not with complete payment of all costs for some 18 months. Support for emigration expenses could come from families, parishes, church organizations, Communities or landlords, but government support would be indirect, mainly through taxes and regulations. So Horton and Robinson failed to get the Government support for total subsidies for emigration, and on that score the experiment was judged a failure.

No similar experiment was ever attempted and so the Robinson emigrations were unique. Because they had so much to prove, Robinson kept exceptional records of every person and his records have been a boon to descendants wanting to learn about their families in the 1820s of Ireland and Upper Canada.

I agree with the view that these emigrants without viable opportunities nearby were prepared to take the offered all expenses paid trip to start a new and bright future for their families. They were driven by hope.

Those emigrants who chose to farm, and this was the major portion although Robinson tried to get some tradespeople and merchants in the mix of 2,024 emigrants, seem to have succeeded in meeting the conditions of the offer. After nine or ten years all conditions had been met and patents were granted to farmers and sons of farmers. Some families remained in farming for several generations even to the present. So most had the knowledge of farming, the previous experience and the skills to succeed. And there were sufficient people of similar backgrounds to ensure the old community cultures would thrive, too.

Elwood H. Jones, 16 May 2025