The History: Understanding the Peter Robinson Emigration

Jump To

The Five Ws

Who: Advocated by Robert Wilmot Horton, Member of the British Parliament and member of the Colonial Office and led by Peter Robinson who had important connections in Upper Canada.

What: The proposal was to completely support a group of poor but worthy Irish people who were attracted to the promise of a better life in Canada. The intent was that the costs would be offset by loyalty to the British and future markets for British goods.

When: Peter Robinson led groups to Upper Canada in 1823 and 1825. The British government never again sponsored emigration schemes that required complete support for all expenses of travel and the costs of establishing farms with rations for fully eighteen months.

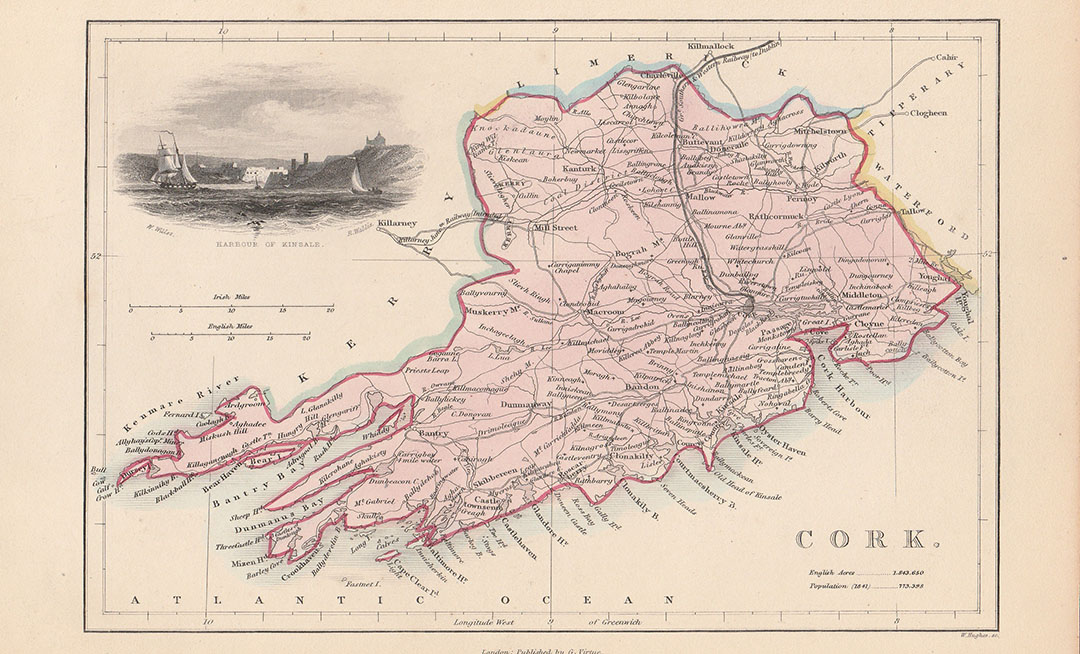

Where: The emigrants were chosen in the Blackwater Valley area of southern Ireland and they were settled in the Ottawa Valley in 1823 and in 1825 they arrived in Nogojiwanong, the future city and many places within what is now Peterborough county and the City of Kawartha Lakes (and some points east).

Why: There were fears that Ireland’s rapid growth in population would outpace its agricultural productivity, and a hope that Canada could balance population and produce on both sides of the Atlantic.

Context: Early 1800's Ireland

Before the Peter Robinson Emigration Experiment

Even before the devastating Great Famine (1845-1852), Ireland was a land marked by profound social and economic challenges, entrenched in centuries of colonial rule and agrarian dependency. The early 19th century was a time of severe hardship for the Irish population, the majority of whom were small tenant farmers and labourers.

While famine certainly was the driving factor of emigration in the 1840’s it was not so in the 1820’s. Much of the emigration push in the 1820’s came from significant economic, social, population, and land factors.

Munster was the breadbasket of the United Kingdom and much of its produce in potatoes, dairy, and crops were imported from Ireland, making local agricultural prices high for the consumers in Ireland and effectively causing issues of affordability which lead to building societal tensions and unrest.

The growing cause of destitution was more closely related to the small acreage farms, landlord plans to create larger areas for more efficient agricultural production, and the cultural legacy of dividing small farms into even smaller farms to accommodate heirs. The inheritance system, wherein land was divided equally among sons, led to increasingly smaller plots which would not sustain larger and growing families.

On top of this, the local political issues caused by landlords and their agents evicting settlers abruptly led to a community response of violence directed at the offenders often by anonymous groups identified as “whiteboys” or followers of Captain Rock, a fictitious figure. Many landlords had influence in London especially since 1800 when Ireland lost its parliament in Dublin in exchange for some representation at Westminster. Some of the Irish influence was in the British cabinet with such figures as the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel.

Another huge factor was extraordinary population growth of Ireland between 1750 and 1830. Economic and social pressures were compounded by this rapid population growth. From 1800 to 1845, Ireland’s population swelled from approximately 5 million to over 8 million. Economists of the time were noting that there was a limit to how much population growth was feasible if it exceeded the ability to expand agriculture.

This demographic boom intensified the strain on the land and resources, leading to dire living conditions for many and went on to spark major political debate in the 1820’s, ultimately becoming a prime factor in Sir Robert Wilmot Horton’s enthusiasm for the Robinson experiment.

Discover more about Ireland to 1830 by reading Elwood Jones’ essay on “Old World Colony”. Click the button below to download and view the essay in PDF format.

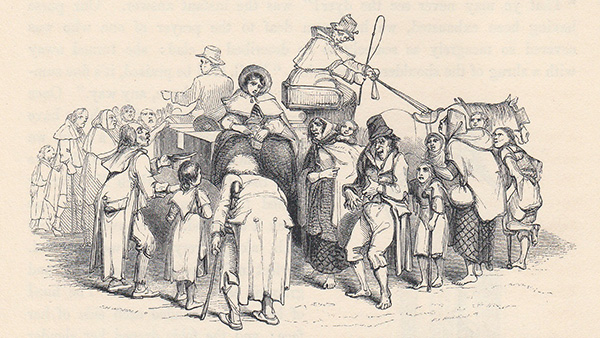

Illustration from Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, &c. by Mr. & Mrs. S. C. Hall

Illustration from Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, &c. by Mr. & Mrs. S. C. Hall Pg.29

The Rockites dealt severely with those who persisted in violating their “laws” against taking farms or even smallholdings from which the previous tenants had been evicted. Numerous murders (sometimes committed with an axe, as depicted in this sketch) and many acts of incendiarism were traceable to evictions in the early 1820s. The large Kilkenny farmer John Marum, a brother of the Catholic bishop of Ossory, suffered a gruesome death (a fractured skull and multiple bayonet wounds) in March 1823 as a repeated violator of this iron Rockite law. – from Realities of Irish Life by William Stuart Trench [London, 1868], facing p. 57

The Right Honourable Sir Robert Wilmot Horton, Bart., G.C.B.

More than any single British political figure in Britain in the 1820s, Wilmot Horton (1784-1841) was responsible for obtaining the support of the parliamentary Committee on Emigration to approve and finance his programme to initiate the emigration of impoverished Irish to Upper Canada. Having gained financial approval from parliament, Wilmot Horton selected Peter Robinson to superintend the two Irish emigrant schemes, which brought about 565 settlers to the Almonte region of the Bathurst District in 1823 and 2,000 more to the Nogojiwanong-Peterborough region of the Newcastle District in 1825. Robert was a first cousin of the poet Lord Byron, their mothers being sisters.

From The Peter Robinson Irish Emigrations of 1823 and 1825 (2015) by Peter E. McConkey

Emigration as a Remedy

The Peter Robinson Emigration Experiment of 1825 is a significant example of emigration as a remedy to the building economic and social challenges Ireland faced in the early 1800’s. Named after the project’s overseer, Peter Robinson, this scheme aimed to relocate over 2,000 impoverished Irish families to Canada. The experiment was adovcated by Robert Wilmot Horton, a Member of the British Parliament and member of the Colonial Office. It was not merely an escape from hardship but also a strategic effort by the British to populate and develop their Canadian territories with industrious settlers who could cultivate the land and contribute to the colony’s growth.

This program was meticulously organized, involving detailed planning and support from the British government. The emigrants were provided with transportation, provisions for the journey, and support for the first 18 months after their arrival, including tools and supplies to establish their new lives in Canada. This support was critical in ensuring the success of the settlers and the sustainable development of the new communities they formed.

Impact of the Peter Robinson Emigration

In Canada, the arrival of Irish settlers contributed significantly to the development of new regions, particularly in Ontario, where many of the Peter Robinson settlers established their new homes. These emigrants brought with them their culture, traditions, and resilience, which enriched the social and economic fabric of their new communities.

The legacy of this early emigration period is still evident today in the strong Irish-Canadian communities and the deep connections between Ireland and Canada. The pre-famine history of Ireland and the subsequent emigration serve as a poignant reminder of the struggles and resilience of the Irish people and their enduring contributions to the global community.

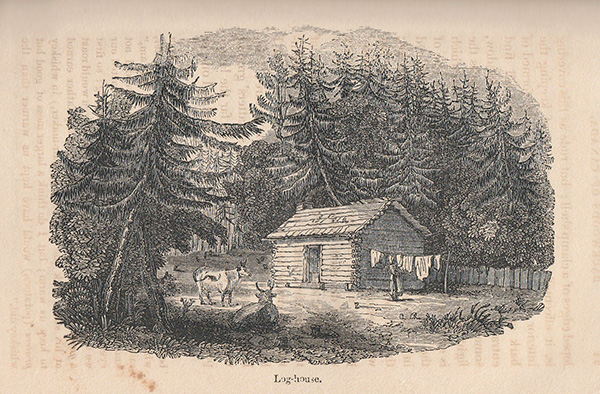

“Newly Cleared Land.”

Illustration from The Backwoods of Canada by Charles Knight

Records and Information

Because this was a uniquely government-sponsored project, the archival records are remarkably complete. It is possible to identify all the emigrants, the ships on which they travelled, and the details of their settlement. The records include the parliamentary reports of the several committees, the records of the Colonial Office, Emigration and Admiralty records, newspaper reports, and the reactions of those they met along the way.

Of great interest locally, Peter Robinson’s archival papers were donated to Peterborough in 1897. Particularly useful are the writings of Catharine Parr Traill who was interested in the experiences of the First Nations and of the botanical wonders she encountered. The local archives have gathered useful accounts by descendants and historians and supplement the records that are in England, Ottawa, and Toronto.

To find out more about these archival records, where to find them, and other resources please visit our Resources and Links page.

Discover More

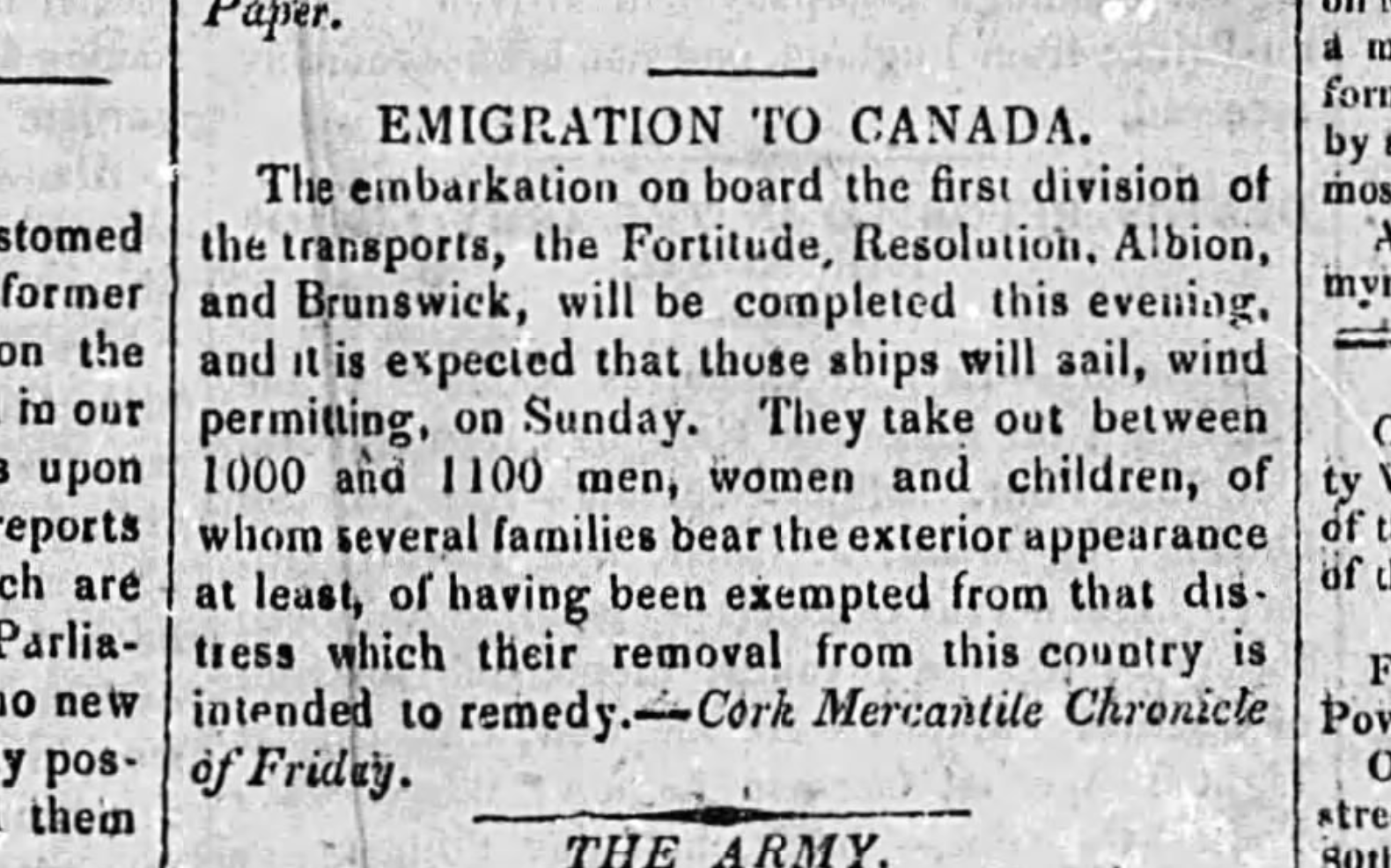

The Waterford Mirror, May 9, 1825, Page 3. via Newspapers.com. Clip page for Report about the Peter Robinson settlers going to Canada 1825 by user lonecrow

“EMIGRATION TO CANADA. The embarkation on board the first division of the transports, the Fortitude, Resolution, Albion, and Brunswick, will be completed this evening, and its expected that those ships will sail, wind permitting, on Sunday. They take out between 1000 and 1100 men, women and children, of whom several families bear the exterior appearance at least, of having been exempted from that distress which their removal from this country is intended to remedy. – Cork Mercantile Chronicle of Friday.“

The Chronological Journey of the Peter Robinson Emigration

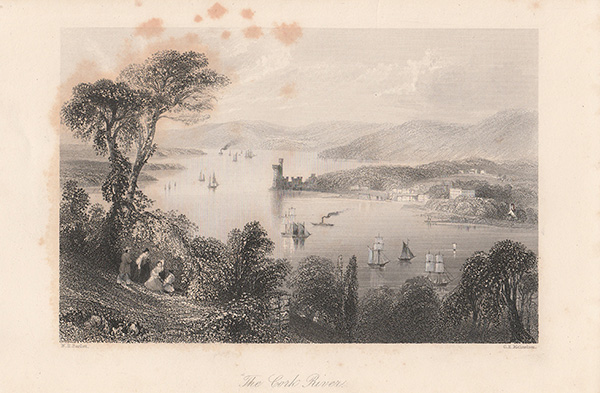

“The Cork River”

Illustration of The Cork River by G.K Richardson and W.H. Bartlett from Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, &c. by Mr. & Mrs. S. C. Hall

Early 1820's

The Context in Ireland

In the early 1820s, Ireland was experiencing severe economic and social difficulties. The majority of the population lived in rural areas and relied heavily on subsistence farming, with the potato being the staple crop. The land was primarily controlled by absentee landlords, and many Irish families faced extreme poverty, inadequate housing, and food insecurity. The rapid population growth exacerbated these challenges, creating dire living conditions and little hope for improvement.

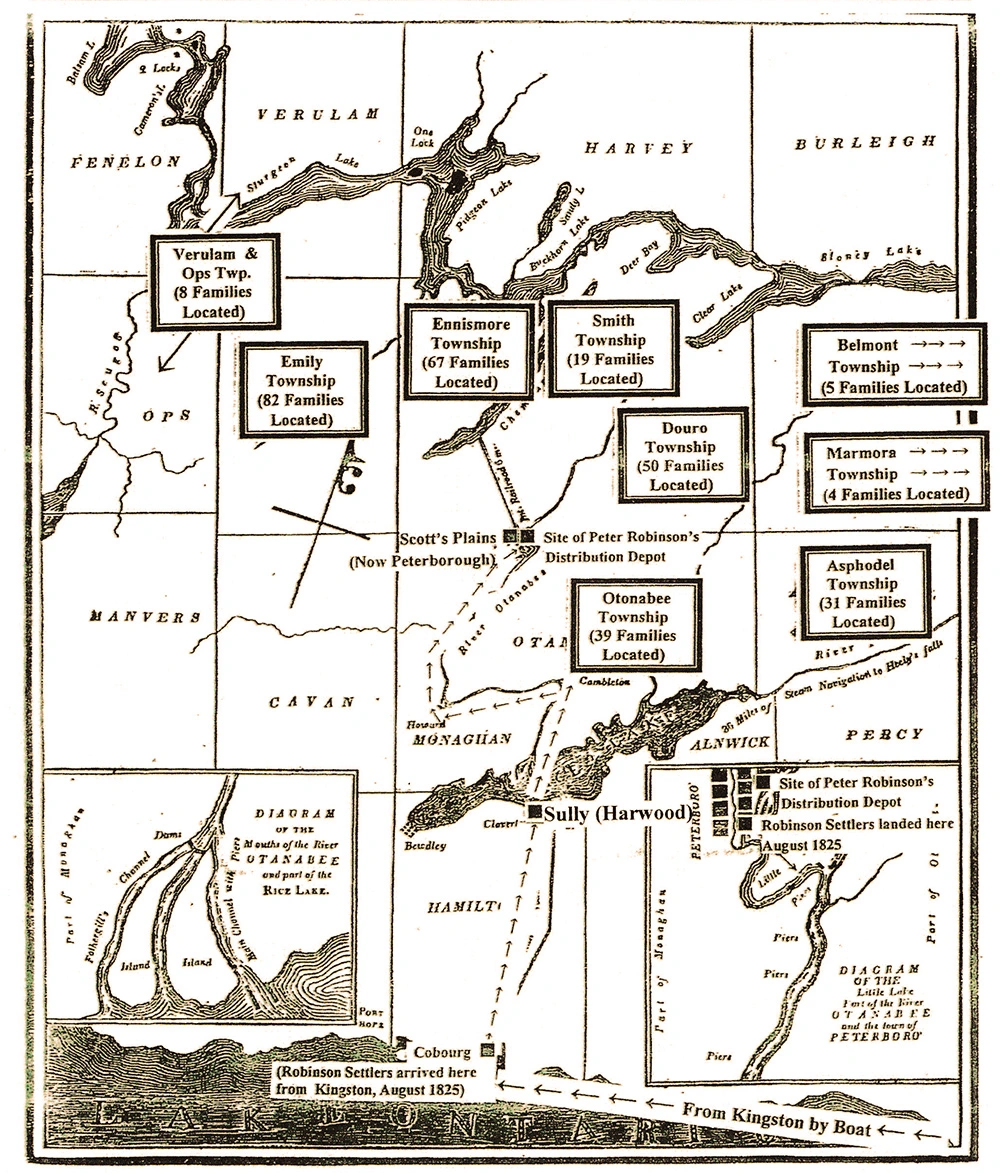

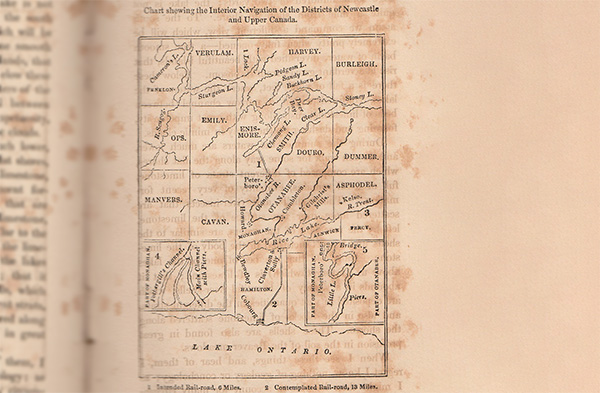

Chart showing the Interior Navigation of the Districts of Newcastle and Upper Canada from The Backwoods of Canada – Charles Knight

1822

The Proposal and Planning

In response to the growing distress, Peter Robinson, a prominent Canadian politician with family ties to Ireland, meets Robert J. Wilmot Horton in 1822. Wilmot Horton asks Peter to superintend the 1st government-sponsored emigration scheme to Canada. The plan aimed to relocate impoverished Irish families to Canada, providing them with land and resources to start anew. The proposal was rooted in the idea of organized, government-sponsored emigration as a solution to both the Irish economic crisis and the need for skilled settlers in Canada.

In 1823, the Emigration Committee of the London Parliament recommends that the House of Commons vote to allocate £15,000 (roughly £2,237,583 or $3,979,239 CAD today) to finance emigration to the colonies, recognizing it as a strategic opportunity to ease the pressures in Ireland while bolstering the population in its North American colonies. Of this, Peter Robinson is granted £9,678 (roughly £1,445,031 or $2,569,880 CAD today) to underwrite his Upper Canada emigration scheme. Detailed planning began, including the selection of emigrants, arrangements for their journey, and provisions for their settlement in Canada.

Emigration to Canada – Memorandum Poster (Cropped)

Copy of LDS Film # 394002 by Carol Robocker-Andersen

1823

Publicity and Selection

With the funds in place, Peter Robinson makes his way to County Cork, Ireland arriving in Fermoy, County Cork on 20 May, 1823. From there, he follows the instructions of Wilmot Horton to consult with prominent figures, seeking recommendations for suitable emigrants that fit the requirements of the scheme.

In early June 1823, Robinson, under authorization of Wilmot Horton initiates publicity to recruit 500-600 candidates for emigration to Upper Canada. Several hundred copies of broadsheet advertising are printed and distributed/displayed in Fermoy, Mitchelstown, Doneraile, Charlesville, Newmarket, Kanturk, Mallow and nearby villages.

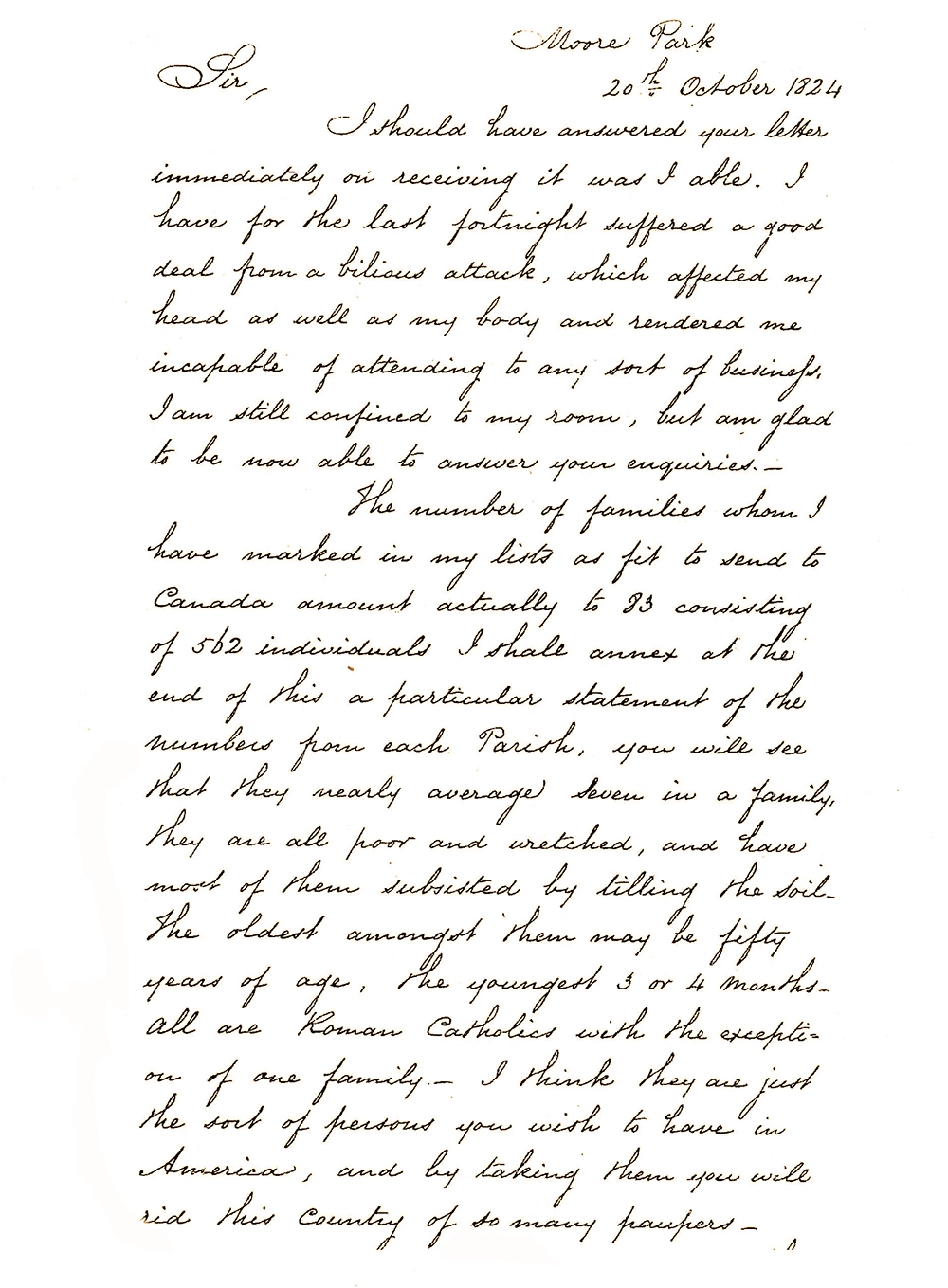

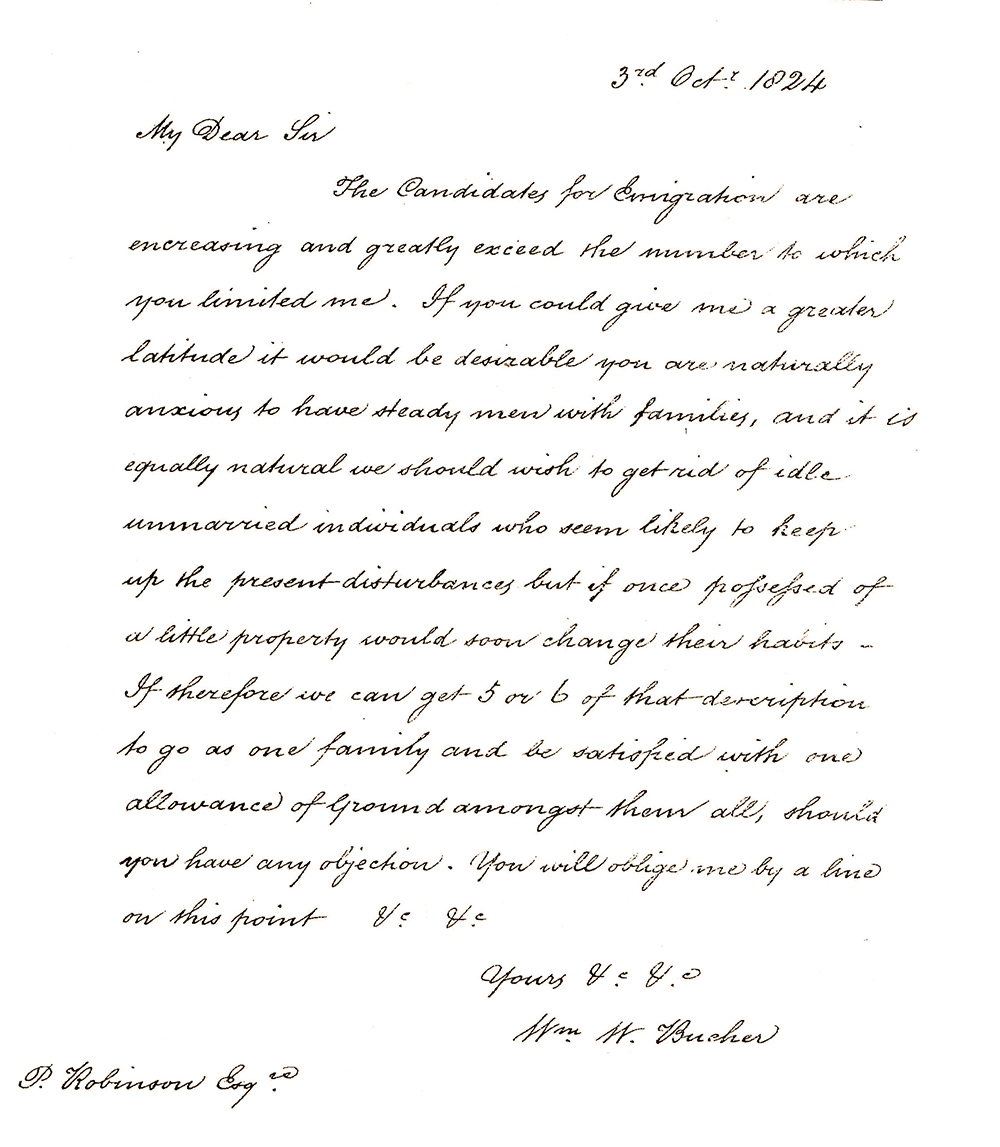

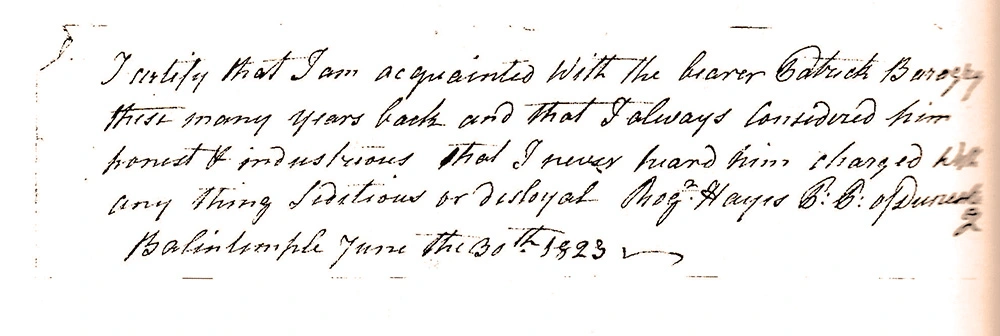

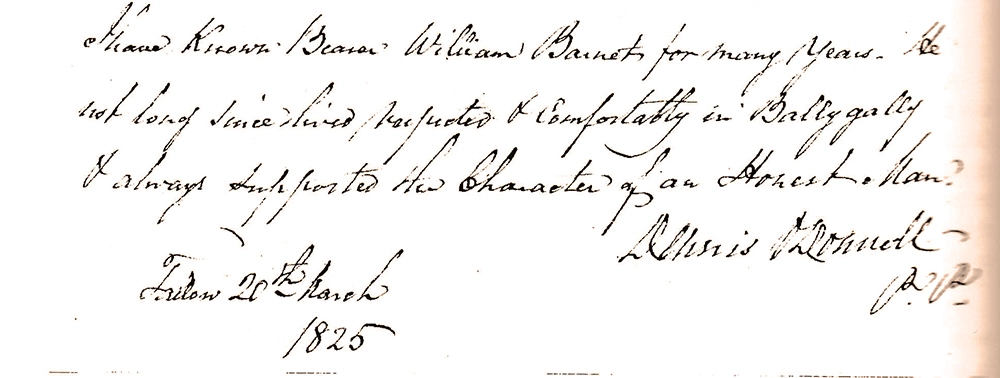

Selection & Recommendation Letters

Click to expand the letter and read a unique piece of history.

1825

The Departure from Ireland

In the spring of 1825, the emigration scheme was set into motion. Peter Robinson arrived in County Cork to oversee the selection process. The criteria for selection included families who were willing to emigrate and had the physical capacity to work on the land. The chosen emigrants came from some of the most impoverished areas, particularly the counties of Cork, Limerick, and Tipperary.

On the morning of May 6, 1825, the first of nine ships, the Regulus, departed from Cobh (then known as Queenstown) in County Cork. Over the following weeks, a total of nine ships set sail from Ireland, carrying 2,024 individuals, including 234 families, across the Atlantic Ocean. The journey was perilous, with the emigrants facing cramped conditions, rough seas, and the constant threat of illness.

“Log-Village – Arrival of a Stage-coach.”

Illustration from The Backwoods of Canada by Charles Knight

Late 1825

Arrival in Canada

The first ships began arriving in Quebec City in late June 1825. The emigrants were processed and given temporary shelter before continuing their journey inland, mostly by steam boat. From Quebec City, they traveled by river and overland first to Kingston, where they stayed for almost a month, and then by water again onto the town of Cobourg eventually making their way to the designated settlement areas in what is now Peterborough County, Ontario.

Upon arrival, the emigrants faced the daunting task of building new lives in an unfamiliar and often harsh environment. They were provided with land grants, tools, and provisions to sustain them for the first 18 months. The land in the Nogojiwanong-Peterborough region, though fertile, required significant clearing and preparation before it could be farmed.

“On Thursday last, 568 Irish Emigrants, including women and children, arrived here [Montreal] in the Lady Sherbrooke Steam Boat and proceeded on their route to Upper Canada yesterday morning. These are the first of the 2000 for whom Government have made arrangements in this country; they are principally from the south of Ireland and are, we understand, to be located in the neighbourhood of the Rice Lake, near the lately settled townships in rear of Smiths Creek. They are accompanied by two medical men, who, we are informed also act in the capacity of superintendents. By habits of industry and good conduct these people may, under the fostering protection of the Government, become comparitively independent, in a country where local prejudices, oppresive rents, and precarious employment do not interfere to prevent their enjoying that portion of competence which renders the mind at ease, and affords a prospect of comfort to the rising generation, for whose future welfare no provision could be made in the country of their ancestors.”

From the Montreal Courant – 1825

1826-1827

Establishing New Communities

Throughout 1826 and 1827, the settlers worked tirelessly to establish their new communities. They built log cabins, cleared land for farming, and began planting crops to sustain themselves. The British government, under Robinson’s direction, continued to provide support, including additional supplies and assistance with land preparation.

Despite the challenges, the settlers gradually built thriving communities. The Nogojiwanong-Peterborough region became a focal point for Irish settlement in Canada. The emigrants’ hard work and resilience laid the foundations for the region’s development and growth.

The Mapped Journey: From the Blackwater Valley to Upper Canada

The Blackwater Valley

This photo captures the wildness of the upper Blackwater Valley and its rugged terrain, which, in the early 19th century, saw violence from groups like the Ribbonmen and the Whiteboys who fought against local English authorities and landlords. Due to the unrest in this region, Robert Wilmot Horton, influenced by English Parliamentarians and Anglo-Irish landlords, directed Peter Robinson to target this area in County Cork for emigration candidates. As a result, Robinson set up his emigration headquarters in Fermoy, at the heart of the Blackwater Valley. Although the focus was on the Blackwater Valley region, Robinson also drew candidates from surrounding counties.

From Cork to Quebec

1823: July 7/8 – Aug 31/Sept 2

1825: May 5/21 – June 12/July 6

The map above shows the initial leg of the emigrants’ journey to Canada, starting from Cork City to Cobh and then across the Atlantic Ocean. Both the 1823 and 1825 emigrant groups, overseen by Peter Robinson, gathered at the docks along the River Lee in Cork. From there, they were taken by small steamer to Cobh (Cove) in outer Cork Harbour, where they boarded transport ships for their transatlantic journey to Quebec, and then to their settlements in the Bathurst and Newcastle Districts of Upper Canada.

The Queenstown Harbour • Cobh, Ireland (ca 1870)

This view of Queenstown/Cobh is from about 45 years after the Robinson emigrations, but the town would have looked similar in 1823 and 1825. Known as Queenstown from 1855 to 1922, the harbour was the departure point for the Peter Robinson emigrations to Quebec. From these docks, emigrants bid farewell to their relatives and friends before setting off across the Atlantic to begin their new lives in Canada. This scene was the last view they had of their homeland.

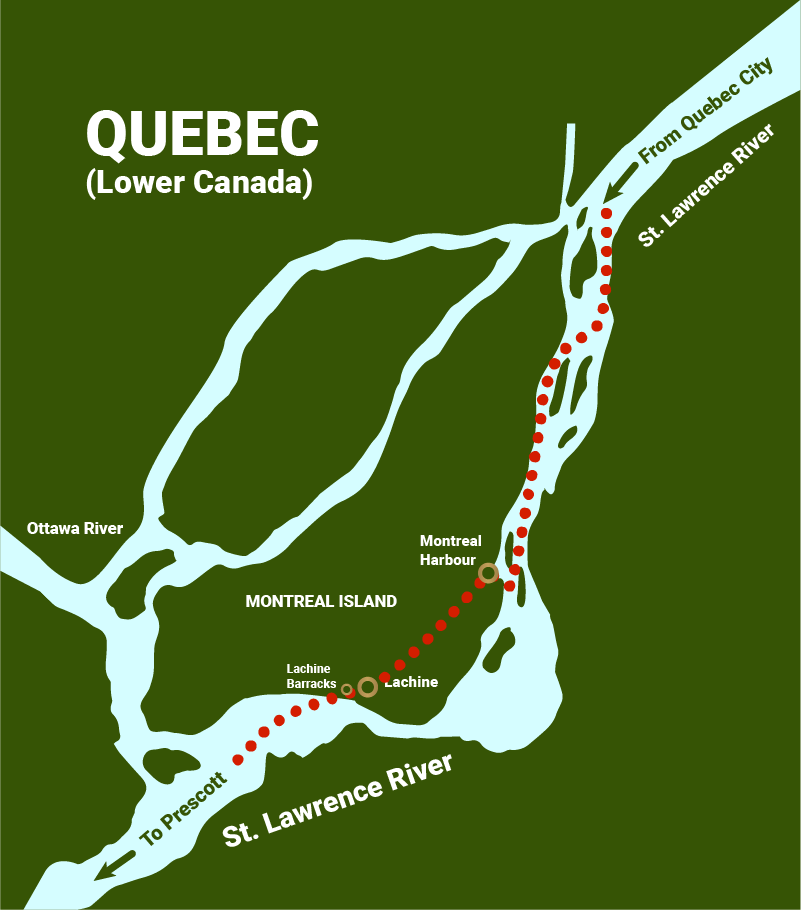

King's Wharf, Quebec City to Montreal Harbour

1823: Aug 31 – Sept 8

1825: June 12 – July 9

This map shows the end of the Emigrants’ transatlantic voyage (Cobh, Ireland to Quebec, Lower Canada) and the beginning of their journey further into Upper Canada (Quebec City to Montreal). The crossing took about eight weeks for the 1823 emigration and around six and a half weeks for the nine ships of the 1825 emigration. According to the captains, the 1823 voyage was uneventful weather-wise, but many emigrants suffered from sea-sickness, having never been on a ship before. The meals were quite different from the simple fare of potatoes they were used to, leading many to throw their food overboard. Children particularly struggled with the Royal Navy’s provisions, often refusing to eat, making them more susceptible to illness. Despite these challenges, the surgeons on board worked diligently to ensure the emigrants arrived in Quebec in good health, and they were largely successful.

Statement of Impoverished Status of Families Applying for Emigration

This letter from May 7, 1825 reads:

We the undersigned certify that the four families who left Cap Clear for emigration to Canada under P. Robinson Esq viz Joseph Shehan and family-Cor[neliu]s Driscoll and family – Michael Driscoll – and Den[ni]s Driscoll and family were in such poor circumstances as to be unable to occupy the small farms which they held heretofore in said Island – and that if they did not obtain their passage over as a gratuity they could never have been other than starving paupers in their native country —

John N. Wright Esq Curate

Joseph Ambrose P P

Note: These families all sailed on the Brunswick.

Quebec to Montreal and Lachine

1823: Aug 31 – Sept 8

1825: June 12 – July 9

From the port of Montreal, the Irish travellers continued to their new homes in the Bathurst District (1823) or in the region of Nogojiwanong-Peterborough (1825). The exhausted travellers walked 20 kilometres (12 miles) from the port of Montreal to the military barracks at Lachine, near the end of Montreal Island. Their baggage accompanied them on carts. At Lachine, they rested for a few days in the old military facilities. Still weary, the emigrants began the next phase of their journey from Lachine to Prescott. For the initial part of this trip, which included navigating the rapids west of Montreal, they travelled by bateaux, rowed by the more able-bodied Irish emigrants and guided by two Canadians familiar with the St. Lawrence. After passing Vaudreuil, the Cascades, and Coteau-du-Lac, they continued by river steamer, arriving at Prescott, where they briefly rested on the grounds of Fort Wellington.

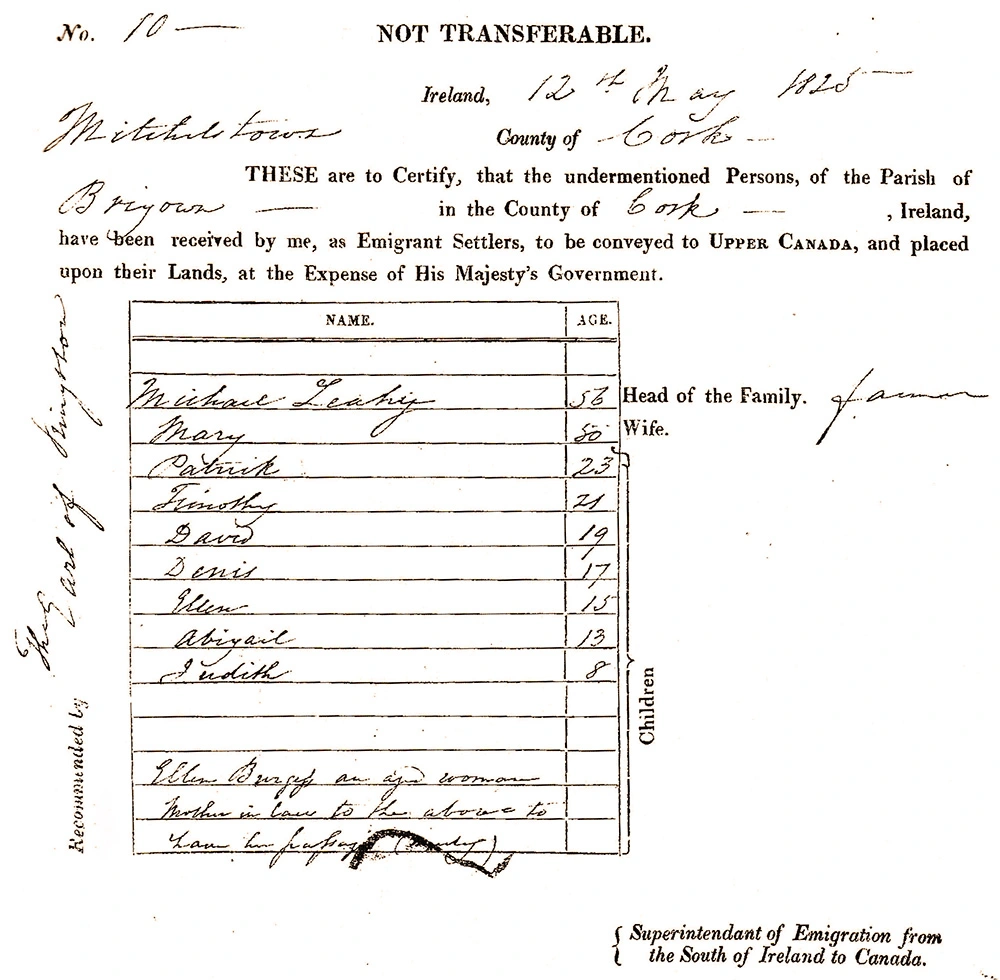

Embarkation Certificate

This Embarkation Certificate from May 12, 1825 details the family information of the Leahys traveling from the Parish of Brigown in the County of Cork, Ireland.

The names are listed on the left and the ages of the family members to the right. As you can see this was a large family.

The lower section reads “Ellen Burgess an aged woman, Mother in law to the above to have her passage (Montg[omery])”

Prescott to Kingston

June 20 – Aug 12

Kingston to Cobourg

Aug 12 – Eng of Aug

The Final Legs of the Journey

The 1825 emigration, led by Peter Robinson, involved almost four times as many people as the 1823 initiative, requiring nine ships instead of two. Robinson had learned valuable lessons from the earlier emigration, leading to several key differences in his approach for 1825:

- The ships embarked two months earlier (May instead of July) to ensure the emigrants could settle in the Newcastle District before winter.

- Robinson brought fewer single adult males and more family units, as most deserters in 1823 were single men.

- The 1825 crossing from Cobh to Quebec was two weeks shorter on average than in 1823.

- Unlike in 1823, Robinson did not accompany the emigrants from Cork to Quebec. Instead, he returned to England and then traveled back to Canada via New York, rejoining the settlers in early August in Kingston. This absence, which lasted for the longest segments of the voyage, was criticized and seen by some emigrants as an abandonment.

- In 1823, Robinson struggled to fill the 568 available spaces, but in 1825, he received nearly 50,000 applications for 2,000 spots. This overwhelming response required a different selection process. Robinson had to rely more on recommendations from landlords and their agents, who screened their tenants. This eased the burden on Robinson and his staff but meant he couldn’t personally verify the suitability of all applicants. In some cases, large landowners might have recommended tenants they wished to remove.

Journey’s End: The Final Stage of the Emigrants’ Odyssey

From Cork, Ireland, to Their New Home in the Newcastle District

The lakefront town of Cobourg on Lake Ontario’s north shore was the launching point for the final 48 kilometre (30 miles) trek to the backwoods of what is now Nogojiwanong-Peterborough. This last leg of the journey posed new challenges. Peter Robinson had to repair the road from Cobourg to Gore’s Landing to make it passable for the wagons carrying the settlers and their provisions.

The emigrants followed the Gore’s Landing Road north from Cobourg, traveling on foot in small groups. They passed Sidey’s Tavern at Coldsprings and reached William’s Tavern along the south shore of Rice Lake. They then encamped at Lot 7, west of Sully’s Tavern, before moving to a shadier, sandier shore at Lot 9.

Robinson encountered another difficulty transporting his emigrants from Sully (Harwood) across Rice Lake to their final destination at The Depot (Scott’s Plains Area/Nogojiwanong -Peterborough). The boats he had brought were unsuitable for the Otonabee River’s shallow shoals, necessitating the construction of a large, shallow-draught scow at Sully (Harwood). This scow ferried the settlers across Rice Lake and up the Otonabee River to Scott’s Mills (Nogojiwanong-Peterborough).

Arrival and Settlement in Peterborough

By early October 1825, the nearly 2,000 Irish settlers from Cork had reached The Depot (supply hub) in what is now considered downtown Nogojiwanong-Peterborough, where they awaited Robinson’s direction to their new homes. The landing site was on the western bank of the Otonabee River, north of Adam Scott’s Mill, where a temporary camp of hundreds of tents was set up.

Over the next few weeks, Robinson assigned each family a settlement location from his log cabin at Water and Simcoe Streets. To prevent settlers from getting lost in the Upper Canada wilderness, guides accompanied each group of four or five families to their designated land. Small log cabins were built on each family’s assigned plot.

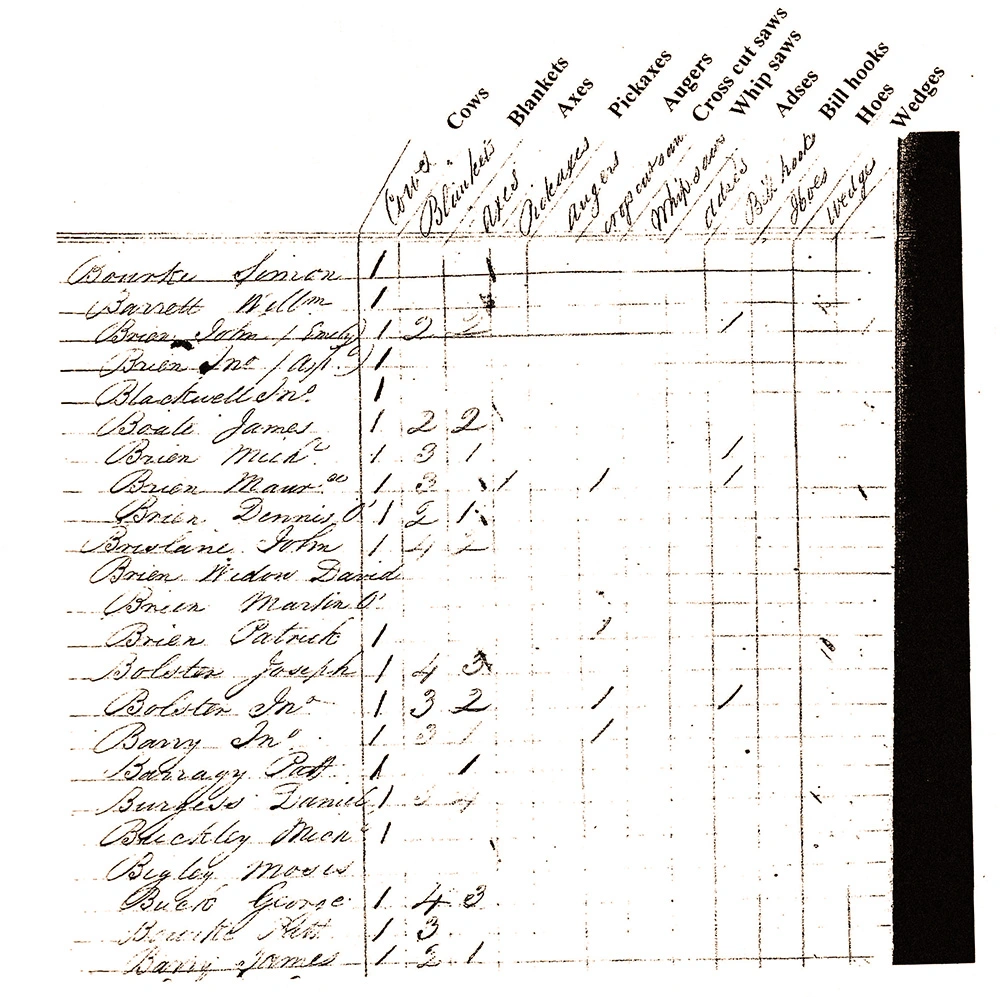

Daily rations and essential provisions were provided to help the settlers survive until they were established. Each family received pork, flour, a cow, farming tools, household utensils, and seeds for planting. Despite these efforts, many settlers fell ill from ague or swamp fever due to malnutrition and the exhausting journey, resulting in high mortality rates and leaving many children as orphans.

By the end of autumn 1825, the major part of Robinson’s work was complete. He had successfully recruited, transported, located, and supervised nearly 2,000 Irish emigrants in the Peterborough region, marking the end of their long journey from Cork to their new home.

Tool allotment chart and transcript provided by Peter McConkey. Click to expand.

Government House – 1825

Located on the SE corner of Water & Simcoe Streets, Nogojiwanong-Peterborough

This plaque reads: “On this site stood the 1825 Government House, the log dwelling and office of Peter Robinson, who assisted 2200 Irish immigrants in settling here by the British Government, and whose name was given to the settlement.”

Fun Fact

Again we extend a huge appreciation to Peter McConkey for his dedication to archiving and researching the history behind the Peter Robinson Emigration. His efforts have been invaluable in gathering the information above. He also graciously allowed us to share his book information with the community through our platform.

Thank you Peter!

For a full look at Peter’s detailed book: The Peter Robinson Irish Emigrations of 1823 and 1825 (2015) please visit Trent Valley Archives in Nogojiwanong-Peterborough, Ontario.

We would also like to extend our heartfelt thanks to volunteers Nancy Towns and Nicole Gagliardi for their invaluable writing contributions. Their work on the Federal funding application has been instrumental, and we appreciate the incorporation of their copy across almost everything we publish, including the website, project descriptions, and media releases. Thank you!

![NINE-SHIPS-Statement-of-impoverished-letter A hand written letter from 1825. This letter from May 7, 1825 reads: We the undersigned certify that the four families who left Cap Clear for emigration to Canada under P. Robinson Esq viz Joseph Shehan and family-Cor[neliu]s Driscoll and family - Michael Driscoll - and Den[ni]s Driscoll and family were in suchy poor circumstances as to be unable to occupy the small farms which they held heretofore in said Island - and that if they did not obtain their passage over as a gratuity fey could never have been other than starving paupers in their native country -- John N. Wright Esq Curate Joseph Ambrose P P](https://nineships1825.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/NINE-SHIPS-Statement-of-impoverished-letter.webp)